Jaroslav Nekuda has been working at the faculty since it was founded. In 1991 he contributed to building the faculty library, which he then headed for 27 years. “It was beginning to look like I would be in ‘office’ longer than the Belarusian president, Lukashenko, so in 2019 I handed the reins over to a colleague,” he recalls with a smile. How does he look back on the past 30 years at the faculty, why does he sometimes feel like a jack-of-all-trades, and what led him to considering launching a general university strike titled “Death to Excel”? You will find the answers in this interview.

What does the Faculty of Economics and Administration mean to you?

For me, it is primarily a community of wonderful people, many of whom are my friends who I respect. I really enjoy having nothing but interesting conversations with them and finding inspiration.

You have been at the faculty since its founding. How do you look back on the past 30 years?

I like thinking about its first few years of existence in particular. Everything was so new and exciting. The faculty was not only the epicentre of the post-November revolution, but it was home to multiple “revolutions” all happening at the same time. By smashing ideological barriers, we gained access to modern knowledge and theories. I still recall the first Western economics textbooks, and their translations, that we got here: they were so novel and fresh compared to the stale old claptrap about the dialectical relationship of the base and superstructure. Digitalization and the “Internets” were knocking at the door.

How did that play out in the faculty’s early days?

At the library we began replacing the card catalogue with an electronic catalogue. I regularly got the frightening idea in my head of what we would do if the electronic catalogue somehow got erased and the card catalogue no longer existed. In 1992 universities first connected to the internet. I light up when I recall that small black-and-white monitor on which I read my first email. That was really something! I’ll never forget a question that one high-level faculty official asked me at the time: “What are you constantly doing with those computers? Are you playing games, or what are they good for?” Today when we lose power at the faculty, it’s as if you were to remove the magical shem from the Golem. The faculty without computers and the internet. Think about that!

Were there any critical moments during the faculty’s history?

There was probably really only one critical moment. When the academic senate approved the establishment of the faculty by the slimmest of margins – by only one vote. Another important event was the development of the project to sell the old building on Zelný trh Square and erect a new building for the faculty. The existence of the latter has enabled our potential to fully develop. Perhaps a local Banksy could spray-paint on the entrance to the building: “Nothing can stop us now.”

How would you describe the faculty’s growth?

Like a spectacular story with a happy end. At the beginning there was a small group of people who in 1990 met in a dark, smoky office at the Research Institute. They argued about the future of the new faculty, and there were no clear, coherent ideas about what would be the best to do and how. Well, and at the end of the story here we have a very modern school, which certainly ranks among the best economics faculties in the country.

I almost felt like a satrap in an Oriental despotism

You founded the faculty library. How do put a library like that together?

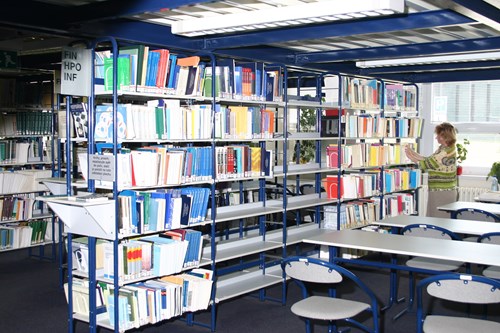

We started off with a few boxes of books that the Faculty of Law gave us and a few foreign gifts. Today, we have more than 80,000 titles. At the time, we had only two permanent employees, and later, two interns. We could basically do everything the way we saw fit. For inspiration, we travelled to Vienna, to the Wirtschaftsuniversität. And then the library was built with its evolution and long-term objectives in mind. It’s been a long road. From the beginning, we also relied on the opinions and needs of our users. For this purpose, we developed many feedback loops, and the second pillar we leaned upon was regularly analysing our data.

If you were to mention the most important events in the library’s history, what would they be?

The most important moment was the complete renovation of the library in 2012, because the “old library” and today’s new library are apples and oranges. One great thing was hiring a young computer science graduate – currently the head of the library – in 2001. Thanks to his qualifications and personal interests we were able to move many things forward in a new way. Progress was also brought by the library’s 2018 transition to the RFID system, which enables users to check out and return books by themselves. Another important moment was when the library was entrusted with teaching Academic Writing, a mandatory course at the faculty. Back in 2010 the course was taught fully online, as the first such class at the FEA, so the coronavirus didn’t catch us off guard, not even a little bit.

The library also created the first open access digital archive of master’s theses in the Czech Republic. What was your motivation for this?

I had the habit of walking through the library every morning. I noticed that the documents that were most often taken off the shelves and left strewn about, and which needed to be constantly cleaned up, were master’s theses. So, I had an idea: what if we digitized them and allowed students to access them electronically?

In 2019 you handed over the baton to your colleague Jiří Poláček, who became the library director. What led you to this decision?

I had been in charge of the library since 1991. As I was approaching retirement age, I began to feel a bit like a satrap in an oriental despotism, sort of like Jean-Bédel Bokassa I. It was beginning to look like I would be in “office” longer than the Belarusian president, Lukashenko. The second reason is a bit gloomier, but not on a personal level.

Would you reveal to our readers what exactly that reason was?

In recent decades, the management of universities and academic activities in generally have become extremely bureaucratic. Form triumphs over substance: we constantly have to study whether we are doing things the right way instead of thinking about which right things we should be doing. Teachers, instead of teaching and conducting research, have to fill in an ever-increasing number of reports, forms, applications, projects, and tables. Among my friends, we call this process, with a little bit of exaggeration, “the Kingdom of Nonsense”. This kingdom however is endowed with the power to coerce and consume its subjects. At one point I even thought about whether a general university strike titled “The End of Filling In Forms” (or alternatively “Death to Excel!”) could lead to the collapse of Czech higher education. Of course, I’m joking...

FEA graduates have little trouble finding jobs

Now you work as a librarian specialist. What are your responsibilities?

Yes, sometimes I feel like a jack-of-all-trades. I do a little bit of everything. I issue opinions on purchases of all new books and subscriptions to journals and electronic resources. I feed data into some information services we offer, like the Book Register, New Publications from Around the World, Journal Contents, the Book Cover Database, and the library’s Twitter account. I also do media monitoring and make sure that required and recommended literature for all courses taught at the faculty are available. On top of that, we conduct various internal marketing surveys and analyses. For instance, we analyse data related to the admissions process and from course evaluations in the MU Information System. Not long ago, we also conducted a student survey titled “Classes and Academic Conditions at FEA MU during the Coronavirus”. We have already spoken about the Academic Writing course. This year we are adding another one, Academic and Professional Writing, intended for students of professional bachelor’s programmes. My job also involves all kinds of “invisible consultation meetings” or looking up information for teachers and user-service-department employees.

You conduct many different analyses for the university...

Yes. I focus especially on the employment outcomes of Masaryk University graduates. In the first half of the 1990s, in cooperation with the then vice rector, Ivan Vágner, we conducted a systematic survey of graduate outcomes, the first of its kind in the Czech Republic. After that point, MU graduate outcomes were surveyed every year from 1993 to 2018, that is, for 26 graduating classes in total. We have also conducted several marketing surveys for the faculty. In 2000–2009 we also worked as an analytical team for BVV Trade Fairs Brno, where we exclusively conducted several hundred surveys of visitors and exhibitors. So, over the last 30 years, more than 250,000 respondents have passed through our hands, so to speak.

Have you observed any trends in graduate outcomes?

I see the fact that an increasingly larger share of graduates is satisfied with what Masaryk University has contributed to their lives as a significant and gratifying trend. In 1993, 71% of graduates were satisfied. Since then, this number has continually risen, hitting 95% this year. Graduates have a relatively easy time finding jobs. They are flexible on the labour market. A growing number of graduates is satisfied with the pay they receive for their work, and they consider their jobs to be promising. They also have a positive view of their career prospects.

I enjoy spinning yarns and being irreverent

You have spent a great part of your life with books. What is your favourite?

If we are talking about academic books, I enjoy ones about sociology, psychology, social psychology, political science, future studies, and the world of information in general. When it comes to recommendations, I have two: Schopenhauer’s Aphorisms on the Wisdom of Life and J. K. Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces.

What other hobbies do you have, besides reading?

I agree with Aristotles’ opinion that life requires movement. Therefore, I try to exercise regularly – by walking or riding my bike. I’m interested in motorsport and racing vehicles. I occasionally ride a Honda 650. I play chess, swim. I like to watch black comedy films and documentaries. I sometimes try my hand at cooking up various would-be Indian dishes. I spend time with my two grandsons, working in the garden and around my house in Ivančice. I also like spinning elaborate yarns and being irreverent. Take, for example, my “dummy-proof tests”, a big hit with our students. Right now, we are developing an educational game titled “Man, Don’t Be a Major Dummy”, which we will experiment with in Academic Writing in the upcoming autumn semester

What would your message be for the faculty on its 30th anniversary?

Keep going!

The interview with Jaroslav Nekuda was led by Kristýna Férová, a student at FSS MU.